Unreported History: the National Convention for the Defence of the Civic Rights of Women, October 1903

This article by Dr Kate Law and Dr Maureen Wright, University of Chichester, founder and lead of Women’s Political Rights, was first published on January 8, 2019. The copyright belongs to the authors and the Women’s History Network.

Read the article in full on the Women’s History Network. Republished below for record, courtesy of the WHN.

It might be fair to say that for many women’s suffrage scholars October 1903 is a date best known for the founding of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) by Emmeline Pankhurst. However, just a week later, in Holborn Town Hall, an event took place which was equally as significant to the British campaign for Votes for Women. Mrs Pankhurst chose not to attend this event, but over two hundred delegates, representing the regional groupings of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies did convene, together with many women from the increasingly organised Trade Union and labour movements. Dora Montefiore, a future WSPU suffragette and a leader among women tax-resisters, complained afterwards that the impact of the National Convention had suffered because of scanty and erroneous account of the proceedings in the ‘dailies’ – those influential arbiters of public opinion. Her response was to publish a fulsome account herself, in the labour journal The New Age.[1] In this she wrote of the new spirit pervading the women’s suffragists, which was one of cross-class cooperation and a move towards an active, disruptive stance where women would refuse to canvass for parliamentary or local candidates at elections and, more importantly, to make the women’s vote a ‘test question’ for parliamentary candidates. This blog will show that there was a move towards militant tactics in suffragist ranks some time before the well-known ‘test question’ aimed at Sir Edward Grey by Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney of the WSPU in October 1905, and that it was agreed by a resolution passed at the National Convention.

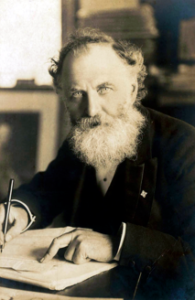

The events that led up to the Convention began in May 1903, with a meeting held at the offices of the radical periodical the Review of Reviews, edited by the veteran of many reformist causes, William T. Stead. Stead, known as Britain’s ‘greatest Muckraker’ for his style of transatlantic progressivist rhetoric, had engaged Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy as the principal speaker of the evening.[2] By this time Wolstenholme Elmy had served the cause of women for over 40 years and had been on the Executive Committee of upwards of twenty feminist organisations. Stead, who had known her since the early-1870s, considered her to be the ‘grey matter in the brains of the…movement’ and although by 1903 she was approaching 70 years of age, her enthusiasm and energy for the cause remained undimmed.[3] Both Stead and Wolstenholme Elmy were avowed pacifists and had held unpopular pro-Boer sentiments during the recently concluded Second Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902. And it was Elmy’s interpretation of events in South Africa that had led her to theorise anew on the issue of women’s suffrage.

‘Outlanders at Home’

Elmy wrote specifically of how the British government’s armed intervention in the issue of the South African ‘Outlander’ franchise could be paralleled to that of British women. Non-Boer males living in the Transvaal and Orange Free State were denied the vote, and Elmy wrote of the invidious position of ‘[o]ur “Outlanders” at home’ – the millions of British women denied citizenship while the army was sent to the Cape to procure it for ex-patriot men by armed intervention.[4] This opened up the possibility of campaigning for the women’s vote by applying the ‘politics of disruption’ – the often violent methods of protest that had been employed by men in Britain throughout the nineteenth century, and which had helped to secure an extension of the electorate from 2% of the male population pre-1832 to 59% in 1884. Wolstenholme Elmy then combined this concept with another, which helped to promote a universal idea of women’s sisterhood on cross-class lines on the premise of something all women shared – their ability to be mothers and to offer their lives for their nation in childbirth as soldiers offered theirs on the battlefield. Elmy thus built her ideology on how motherhood impacted on a crucial element of the requirements for citizenship – ‘the appeal of physical force’ based on ‘physiological argument[s]’.[5] She reasoned mothers had the ‘superior claim’ to citizenship, even though it was contended women did not possess the physical strength to fight for their country. Any woman who had emerged from child-bed, Elmy claimed, had more than enough strength for anything.

British elites had become increasingly concerned by the poor health of the working-class recruits to the armed forces as the war progressed, and so Elmy’s argument had a pertinent and timely edge. She had lived her life close to working class women – her husband Ben employing many local women in Lancashire and Cheshire during his career as a textile-mill owner and watching them suffer in times of economic crisis. Wolstenholme Elmy also knew that local labour movements and women’s trade unionism were, by the Edwardian years, gathering together women who were not afraid to fight for what they believed to be right. She correctly judged too that an alliance between the experience of the middle-class leaders of the suffrage campaign and the determination of the working-class women of the labour movement in northern British cities might be just what was needed to push the Votes for Women issue forward.

By the summer of 1903 Wolstenholme Elmy and W. T. Stead were working closely in co-operation with the North of England Society of Women’s Suffrage, headed by Esther Roper and with Eva Gore-Booth, Secretary of the Women’s Trade Union Guild, to push forward plans for the Convention. Although the event had initially been underwritten by Stead and John Thomasson, a long-term supporter of the women’s cause, thanks to the diligence of Edith Palliser of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) it was that organisation that agreed to host the gathering. Delegates attending included members of the Leeds Tailoresses’ Union, headed by Isabella Ford and Annie Leigh Brown spoke on behalf of the Union of Practical Suffragists. Eva McLaren, who had married into the radical Bright family and was a notable member of the Women’s Liberal Federation, chaired the opening sessions.

The National Convention

The Manchester Courier noted that McLaren intimated that the event should be reported as one for ‘women’, as ‘it is by this designation that the [delegates] prefer to be described’. Perhaps this was a conscious choice to eschew the classic, middle class, ‘ladies’ who had previously made up the majority of active suffragists.[6] These few words open up the issue of cross-class cooperation more specifically and highlight the fact that the delegates were looking for a universal recognition of women’s contribution to national life – rather than to the party political allegiances which had dominated the suffrage movement hitherto.[7] How this shift must have gladdened Wolstenholme Elmy’s heart, for all her campaigns had been conducted from a resolutely non-party perspective and based solely on the grounds of justice and humanity. For her friend Dora Montefiore though, the socialist perspective was critical. Working women, she wrote, ‘are moving, and [they] are in earnest’ – openly critical that their causes seemed to lie behind those of the male, ‘enfranchised members’ of British Unions, even though they paid proportionally more to support socialist candidates to Parliament and were active in canvassing on their behalf.[8] As Montefiore foresaw, it was indeed these women who would ‘furnish the weight and the force which w[ould] drive home to the consciousness of Parliament the necessity for giving equality to the women of Great Britain’.[9] Fifteen years and a World War intervened before that prize was won, but it was the National Convention which first harnessed the co-operation between the sisterhood of all classes and which demonstrated that the rhetoric of militancy was moving through the suffragist ranks – years before the rousing speeches of the militant suffragettes were aired.

It was not only confrontational rhetoric, though, that shone forth at the National Convention, but the first stirrings of a combative approach to practical politics too. The Convention passed a resolution to make women’s suffrage a test question for parliamentary candidates and Stead informed the audience that for a candidate to answer in the negative would be to imply that ‘if women [were] not fit to vote they [were] not fit to canvass’. Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy went further, challenging the view that women were too fine, too delicate and possessed of too much sensibility to engage in the political milieu. She wrote:

Then in the name of decency let him [the candidate,] refuse to allow his committee to appeal to women to canvass for him, or to do any of the ‘unwomanly’ work of electioneering, in order to secure his election. If she must defile herself with politics, even to help her country, do not ask her to do the dirtiest work of politics – canvassing and electioneering – merely to help you to the attainment of your own personal ambition.[10]

Wolstenholme Elmy realised the hypocrisy of some men in this matter, for it had been a cultural commonplace for women to engage in the practical work of canvassing at election time, but by urging them to refuse, the National Convention had set in place the beginnings of the ‘politics of disruption’ which was to categorise the suffrage cause thereafter. For the NUWSS too, the Convention was especially significant, and it brought together, under a common umbrella, the previously ‘almost completely autonomous’ regional suffragist groupings.[11] In December 1903, a Committee agreed to the setting up of NUWSS Election Committees in each parliamentary constituency, thus spreading the focus away from the metropolis into the regions. One hundred and thirty-three Committees were thus inaugurated, raising monies for the central Society to fight the coming General election, and 415 pledges of support were given by prospective candidates.[12] Even though the North of England Society continued to struggle for funds as did others, a mood of increasing confidence and collaboration was spreading through the movement in the weeks following the Convention. Women were coming to see and to understand the reasons for their own oppression. They also saw how this might be overcome if they took to the streets to challenge ‘a State which subjects them ruthlessly to taxation while scornfully refusing them representation’ and failed to understand that healthy, independent and educated women had power to aid the nation.[13] They were poised to claim their rights and it might be pertinent to consider, therefore, just how far the Women’s Social and Political Union truly originated suffrage militancy – even though and many women chose to continue the constitutionalist path.

Dr Maureen Wright is an Associate Lecturer in History in the Institute of Humanities, University of Chichester, UK. She is also founder and lead of Women’s Political Rights, an on-line platform for discussions of women’s rights & women’s suffrage. Her major publications include the first biography of aethist-Suffragist Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy and a number of peer reviewed articles on biographical methodology & suffrage topics.

*For a fuller account of this topic see: Maureen Wright, Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy and the Victorian Feminist Movement: the biography of an Insurgent Woman (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2011).

[1]Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (London: E. Archer, 1927): 43. Also, Dora Montefiore, ‘The Women’s National Convention’ New Age, October 22 1903: 683-4.

[2] W.T. Stead, ‘Honour to Whom Honour is Due’, Review of Reviews 1910, September: 223.

[3] W.T. Stead, ‘Honour to Whom Honour is Due’: 223.

[4] Ignota [pseudonym of Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy], ‘Our “Outlanders” at Home’, Manchester Guardian, August 22, 1899.

[5] Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp and Darwin D. Jorgensen, ‘Physiology and Physical Force: The Effect of Edwardian Science on Women’s Suffrage’, Southern Communications Journal 81, no.3, (2016): 136-55, 137.

[6] Anon, ‘Civic Rights of Women’, The Manchester Courier, October 17 1903.

[7] The National Society for Women’s Suffrage was fractured in December 1888 because of a move by some members to ally with women’s political organisations directly. The caused outrage, with some members exiting the hall in protest. Wright, Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy: 136-7.

[8] Montefiore, ‘The Women’s National Convention’: 684.

[9] Montefiore, ‘The Women’s National Convention’: 684.

[10] W.T. Stead, ‘Interviews on Topics of the Month: “Women and the General Election: Mrs. Wolstenholme Elmy.”’, Review of Reviews, December 1905: 600-1.

[11] Leslie Hume, The National Union of Women Suffrage Societies, 1897-1914 (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2016 [first published 1982]): 22-3.

[12] Hume, National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies: 23.

[13] William T. Stead, ‘The Awakening of Woman’, The Review of Reviews October 1903: 339.